Introduction to the Project

For information on the structure of the corpus click here.

- WELCOME

- WHAT IS GASCON?

- THE PROJECT

- HISTORICAL CONTEXTS

A PERSONAL NOTE

The Linguistic Corpus of Old Gascon began as a simple tool that I developed for my own research on the medieval language. In some ways that is what it remains today. However, I was convinced by a number of people who had an interest in Gascon that it might be useful to have at least some of this material more broadly available. This site is the result of those requests.

Designing a web site and preparing the texts for this sort of presentation has turned out to be a much larger undertaking than I expected, and there is much work left to be done. Not all of the texts I have prepared are posted here at this time, and many of the instruments that I have been using to analyze the data, including concordance tools, are not yet available here. However, I trust that even in its current state the Corpus will be of interest to those who are curious about earlier forms of Gascon.

Database functions are currently unavailable as a result of modifications made to servers at my university at the time of my retirement and move to France. I expect to be able to repair these problems and to add new texts in the coming months of 2021.

If you have suggestions for improving this site and the tools it offers, or if you find errors in the material here, please do not hesitate to contact me. Feel free to write in English, French, or Occitan. You need not be a professional linguist to comment and make suggestions.

Thomas T. Field (tfield@umbc.edu)

I am grateful to the following people who provided suggestions and advice as this project was under development: Peter Ricketts, Marc-Olivier Hinzelin, Patrick Sauzet, Jean Salles-Loustau, Kathryn Klingebiel, Jean Lafitte, and Jean-Louis Fossat.

For their help with the early stages of this online project, I would like to thank the following UMBC students who worked on the Bordelais texts that first served as models for text presentation: Scott Gautney, Allison Isberg, Sandra Lamplugh, Colin Leach, Caitlin McAnallen, Stephanie Smith, Ariana Uffman, and Bryan Wilkinson. Other participants include Michael Costa, Kelly Dunn, Aureanna Hakenson, Ryan Kotowski, and Jessica Willis. I would also like to thank Nagapradeep Chinnam, who prepared the verb database tool.

Strabo and Caesar first noted the distinctiveness of the area that is today the Gascon linguistic domain. De Bello Gallico contains the following description:

The whole of Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, and the third a people who in their own language are called ‘Celts’, but in ours, ‘Gauls’. They all differ among themselves in respect of language, way of life, and laws. The river Garonne divides the Gauls from the Aquitani; [...] Aquitania reaches from the Garonne to the Pyrenees and that part of the ocean nearest Spain. It faces north-west.

Caesar, The Gallic War, I, 1

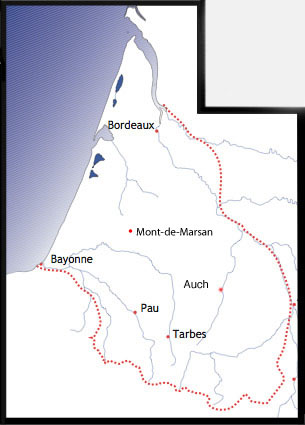

Gascon, spoken today (though less and less frequently) in south-western France and the Aran Valley of Spain, is the result of the continuing use of Latin in the territory of the Aquitani. Caesar’s brief note points out the linguistic and cultural specificity of this original ethnic group and provides a sense of its geographical setting. In fact, the Garonne River is still the approximate northern boundary of the Gascon linguistic domain. The indication that this region “faces north-west” is relevant, too, since the Gascon lands have traditionally been oriented toward the Atlantic. The traditional criteria for defining the Gascon linguistic area are given here. For more information on the general context of this domain see the following presentations:

1. The geographical setting of Gascon

2. The political setting of Gascon

In most respects Modern Gascon resembles Occitan and Catalan; its linguistic peculiarity derives in large part from a series of very early phonological changes. Chambon and Greub (2002) have demonstrated that the distinctiveness of Gascon was clear as early as the 6th century and that its primary characteristics, as they are understood today, were already in place at that time.

3. The linguistic setting of Gascon

There is a general consensus that these traits are related to the substratum upon which Latin developed here. The Aquitanian language, mentioned by Caesar, has left relatively few direct traces, mainly toponyms, anthroponyms, and theonyms in Imperial Roman inscriptions (see Gorrochategui 1995). Nearly all of these seem clearly related to Basque. There is evidence, too, of Iberian names in this region, but the overall weight of the evidence (both linguistic and cultural) suggests an ethnic community in the Aquitanian triangle that was distinct from the Iberian areas to the east. Trask 1997 claims unequivocally that Aquitanian was the direct ancestor of modern Basque and that it is not related to Iberian. Michelena’s account of the history of Basque shows that a number of the peculiar developments that served to distinguish Gascon from other forms of early Romance were actually taking place in Basque at the same time.

The standard scholarly work on Gascon, with a focus on the Pyrenean zone, is Rohlfs (1970). An overview of the entire Gascon domain is provided by Massourre (2012).

For information on the debates about the status of Gascon as a separate language, click here.

Chambon, Jean-Pierre and Yan Greub. Note sur l’âge du (proto)gascon. Revue de linguistique romane 263-264 (2002): 473-495.

Gorrochategui, Joaquín. The Basque Language and Its Neighbors in Antiquity. In Hualde, José Ignacio et al., eds. Towards a History of the Basque Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1995, p. 31-64.

Massourre, Jean-Louis. Le Gascon, les mots et le système. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2012.

Michelena, Luis. Fonética histórica vasca, 3rd ed. San Sebastián: Diputación de Gipuzkoa, 1990.

Rohlfs, Gerhard. Le Gascon: Études de philologie pyrénéenne, 2nd ed. Pau: Marrimpouey Jeune, 1970.

Trask, Robert. The History of Basque. London: Routledge, 1997.

The Linguistic Corpus of Old Gascon has as its goal the construction of a text database that will facilitate the study of language and culture in Gascony from the early 12th century to 1500. The content of such a collection of early texts is potentially enormous: thousands of Gascon texts exist in the archives of France, many of them unpublished. While some have been edited, particularly in regional journals of the late 19th century, many of these are no longer easily accessible. As a result, the researcher who wishes to investigate linguistic or historical problems like language change, practices of literacy, the economics of marriage, or the evolving role of notaries in this part of Europe is faced with a significant problem of documentation.

It is our hope that the Linguistic Corpus of Old Gascon will help to remedy this deficiency and that it will serve to stimulate new research on one of the most poorly understood regions of the Medieval Romance world.

The information provided here is intended to serve as an informal guide to those who wish to understand the history of Gascon and the contexts within which the texts originated. At a later time, additional material will be added, including representations of the relative importance of the different text-production centers over time.